When armed men chant “Allahu Akbar” while murdering civilians, what exactly are we supposed to call it?

That question should be unnecessary. And yet, once again, after Christian farmers were slaughtered on their land in central Nigeria, much of the international commentary has reached for euphemisms instead of truth.

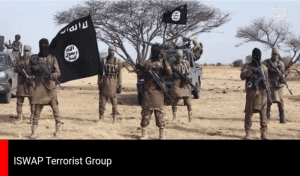

Nine farmers were killed in less than 24 hours in Benue State. They were ambushed while harvesting crops. Witnesses report the attackers spoke Fulfulde, carried firearms and machetes, and shouted Islamic slogans as they attacked. In the aftermath, entire communities fled, leaving their homes and farms behind. Residents say hundreds of armed militants now occupy the land.

Still, the violence is routinely described as communal, environmental, or economic.

Apparently, even shouted Islamic slogans are no longer enough to qualify as religious violence.

This raises a disturbing question: What is the threshold?

If chanting an explicitly Islamic declaration while killing Christians does not meet the standard, then the standard has been rigged to exclude the truth.

The pattern is not ambiguous. The victims are overwhelmingly Christian. The communities are targeted repeatedly. The attacks coincide with planting and harvest seasons. The perpetrators do not steal crops and leave—they remain, occupying farmland and preventing residents from returning. This is not chaos. It is strategy.

Yet naming ideology has become taboo.

Western institutions seem far more comfortable attributing mass violence to climate change than to belief systems. The result is a moral sleight of hand: ideology disappears, accountability dissolves, and victims are left unprotected.

Imagine the reverse scenario. Imagine armed men chanting Christian slogans while killing Muslim civilians and seizing land. No outlet would hesitate to identify the religious motivation. No analyst would rush to explain it away as a “resource dispute.” The language would be immediate and unambiguous.

But when Christians are the victims, clarity suddenly vanishes.

This asymmetry is not accidental. It reflects a broader unwillingness to acknowledge religious persecution when it does not fit approved narratives. Christianity is often treated as culturally dominant—even when its adherents are poor farmers being driven from their land at gunpoint.

Nigeria’s Middle Belt tells a different story.

Here, religion determines who lives safely and who must flee. It determines who can farm and who starves. And it determines whether violence is confronted—or endlessly reclassified and swept under the carpet.

Calling these attacks “farmer–herder clashes” is not neutrality. It is intentional misdirection. Herding does not require an armed militia. Climate stress does not produce coordinated armed occupations. And poverty does not cause men to chant religious slogans while executing Christians.

Words matter because policy follows language. When genocide is mislabeled, the response is misdirected. Mediation replaces protection. Dialogue replaces justice. And the killing continues.

If “Allahu Akbar” shouted during an attack on Christians does not qualify as religious violence, then the phrase has been stripped of all meaning—or the definition has been deliberately narrowed to avoid uncomfortable conclusions.

Either way, the cost is paid in blood — the blood of innocent Christians.

Until we are willing to call religious violence what it is—no matter who commits it or who suffers it—Christians in places like Benue will remain displaced, unheard, and unprotected from the Fulani Ethnic Militia.

And the world will continue pretending not to understand why.